Aesthetic Judgment and the Modern Era

by Andrew Swensen

I still marvel while holding a jump drive. Sixteen gigabytes rest on a fob attached to a keychain, available for a few dollars in the checkout aisle at the local Office Depot. For me, it redefines Blake’s idea of the “world in a grain of sand,” because sometimes it seems as if the world – or at least a large piece of Google Earth – could fit on there. Yet I seem an outlier in my marveling as this little modern miracle has become a commonplace taken for granted, and our culture and our conversation suggest that new wonders should be unfolding on a daily basis. We love our devices and seem to have grown addicted to rapid innovation to the point where we expect always the new.

In our era of fascination with technology, it only seems natural that our art would reflect what has become the spirit of the age. Art comments on our dependence on technology and also reflects the imaginative spirit with which it can be applied. It is interesting to watch how innovations in the hard sciences become innovations in the humanities. Robotics, software engineering, digital information storage and retrieval have all become tools of the trade for artists. Yet this contemporary situation has a couple of traps.

Perhaps most conspicuously, possessing advanced technology does not equal possessing artistic proficiency or creativity. Art requires training typically and discipline always. We have all heard the stories about how this painter never went to art school or that director never went to film school, and technology only fuels these models of achievement without effort, the equivalent of counting on the lottery as your future investment portfolio. Such cases are not reliable plans for artistic success. I often think about what has happened to photography and the moving image in this context. Someone who buys a MacBook with iPhoto and iMovie — or their more strapping cousins, Photoshop and Final Cut — has gained no skill in making pictures or movies. They have a tool, and a very powerful one. These tools do have a lot of magical bells and whistles that compensate for things once done by skilled people, and getting nice exposure, color saturation, and so on have all become easier. Yet that still does not make someone a good photographer or filmmaker.

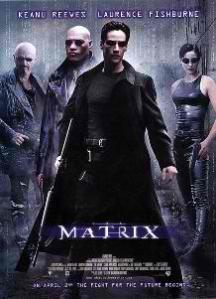

A second liability born of technology lies in the predilection to use fanciful tools because they can dazzle an audience with marvels never before seen. In an article a few years back, I identified this phenomenon as the “Matrix Effect.” Here you had a movie, The Matrix, that examined our interconnectedness with technology, and sure enough they were going to use the most sophisticated technology in its imagery. Then, as soon as people saw those amazing slow-motion images of Keanu Reeves dodging bullets as they warped the air around them, everyone wanted to do it. Yet so often people seem to neglect that a film still rises or falls on issues of excellence – the presence or absence of quality writing, acting and directing – and not merely on the novelty of visual images. Novelty fades; great art does not.

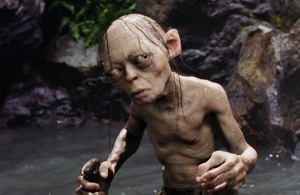

Gollum (Publicity photo, www.lordoftherings.net)

To the Matrix Effect let’s add the Jar Jar Binks/Gollum Corollary, which goes like this: just because you can do something does not mean that you should do something. When George Lucas returned to his Star Wars series in the 1990s, computer-generated imagery had become the marvel of the day. He decided to make an entire character with this wonderful new ability, and surely Jar Jar Binks looked like nothing anyone had seen before. The problem was that when technological marvels met narrative art, they still did not add up to an engaging character. Though Jar Jar Binks has at least one defender in Roger Ebert (whose opinion I value highly in film), most have deemed the character a failure largely because fascination with technology usurped narrative art. Some have even used words much more caustic than “failure.” On the other side of the coin is Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. Similar marvels were used to create the conflicted and mutated character of Gollum, but in this case new technology served successful character creation and narrative artistry. The films won a long list of awards and accolades, and Andy Serkis, the actor who provided the performance that was digitally manipulated into the character on screen, attracted his own acting nominations and awards.

The lesson is not that technology is bad or good, but rather that technological sophistication does not equal artistic success. We apparently sometimes confuse “new” with “good.” It is the artistic version of our increasing dependence on Powerpoint, where a spectacularly animated slide show still does not equal a content-rich presentation. Innovation itself must be subjected to the same rigor of aesthetic judgment that we have historically used for the all other aspects of art making. Some technological innovations have unleashed artistic thunder. They have been revolutionary in opening new worlds to us. Yet strangely, in my opinion, the recent innovations have not been the most influential.

Edison’s tin foil phonograph (Photo: U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site)

I will take three others, which I present in chronological order and not necessarily in order of importance. First, few technological innovations have so completely transformed an art form the way that the invention of the piano changed music. Yes, put Bartolomeo Cristofori up there in the great pantheon of merging art and technology in brilliant fashion, and for those of you interested in learning more on the subject, I heartily recommend Stuart Isacoff’s A Natural History of the Piano. Second on my list is the invention of the camera. Once we had the ability to capture a visual image of the external world, thanks to the magic of silver salts spread on glass and later celluloid, then our world changed. It would be a few more years before a new art form was born, largely thanks to Alfred Steiglitz who took a technology and made an art of it. The third for me is Edison’s phonograph. Recording sound changed music and our experience of it forever. Incidentally, combine innovations number two and three, toss in some more whizz-bang technology to make photographic images flash by at a rate of 24 times per second, and you have what has become the dominant art form of the twentieth century and of our age: cinema.

Many other innovations have emerged from the technological world and found their way into the arts: the synthesizer, video, MacPaint. Even the theremin. Many more are coming soon, and I put my bet on this: the next great thing will come out of the world that we now call “gaming.” The name “gaming” is an unfortunate handicap for interactive, multi-sensory experiences, and a second handicap is the market demand to use this technology primarily to make big explosions in virtual worlds populated by teenage boys. Yet some day soon, someone will transform the nature of narrative art from what we know now into something qualitatively different, much in the way that film supplanted the novel. Yes, we will still have novels and films, but something new is approaching, in which the audience will drive narrative plotting in unprecedented ways.

The key for us nonetheless lies in aesthetic judgment. Yes, it will be new. Yet let’s also demand that it be good.

Bartolomeo Cristofori, Grand Piano. Florence, Italy 1720 (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

_____

Links of Further Interest:

Other articles from The Muse Dialogue, Vol. 1, No. 10: Art and Technology

An NPR review of Stuart Isacoff’s A Natural History of the Piano

The Entertainment Technology Center of Carnegie Mellon University

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

- Aesthetic Judgment and the Modern Era | The Muse Dialogue

Andrew, looking at that beautiful piano, i am thinking that aesthetic judgment has an element of usefulness, of valuing what the object can do in it. And that resonates for me with value in the deeper sense–something more central to us than big explosions (a nice sentence).

Linda F