The Art of Administering

by Marc Giosi

Lately I have been asked with more frequency to give presentations to students and peers about various facets of my job: fundraising, marketing, artistic programming. More often than not, the questions that follow are predictable and have easy “right” answers. “How do I get more followers on Facebook?” “How should I approach a presenter with a unique project?” and so on. Last fall at an arts career seminar, however, a young student asked a question that has had me thinking for over a year: “How has your career and education as a performer influenced your work as an administrator?” Such a subjective question no doubt has a plethora of different answers. An administrator with a painting background will likely have a different opinion than an administrator trained in the theater. For what it’s worth, here is what this classically trained pianist thinks.

Art is neither outside politics nor outside administration. Everything obeys and everything has coordination, so it is much easier to work with any kind of art: both an exhibition in a picture gallery and a production in a theater. Thus, if you wish to find support, it is worth contacting mba essay writing service first and understand the objectives, methods, material engagement and HR.

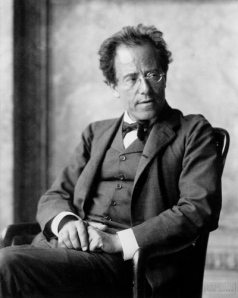

Apart from his artistic success as a brilliant composer and conductor, Gustav Mahler was a well known and effective arts administrator in his day. His tenure as the director of the Vienna Hofoper was tumultuous but largely seen as a success after he settled various labor disputes and brought the organization out of long-term debt.

Efficiency

Having had a modest performing career of my own and knowing what it feels like to be alone on a stage in front of an audience, I feel especially sympathetic to musicians’ needs, and an intimate knowledge of the art form creates clearer and faster lines of communication between performer and presenter. Anyone can read an artist’s technical rider to prepare for a concert, but what if a young group lacks a rider? Or what if an inexperienced manager doesn’t spell everything out on behalf of their client? Things like providing an adequate piano for a musician off stage while the concert grand on stage is being tuned or offering a cellist an adjustable piano bench instead of a straight-backed chair might seem minor but will go a long way to ensure a successful concert. Those examples might seem obvious to many people reading this, but perhaps not to an artistic programmer with a background in sculpture who oversees a small multidisciplinary arts center. (I would never pretend to know what an actor needs to give a live performance. Just lights and a stage, right?)

I once had the experience of working under someone who had years of experience in events management, but not specifically in classical music. He had many strengths in areas like marketing and fundraising, but concert management was not one of them. I vividly remember one instance when a string quartet showed up for a performance and he had arranged all four chairs and music stands in a perfect straight line across the stage, and not the traditional semi-circle that string quartet enthusiasts rightfully anticipate. Resetting the stage took all of 30 seconds, a minor nuisance, but the embarrassment of the moment has stuck with me.

I have found that my knowledge of the classical music canon has made me a more efficient grant writer as well. If my musician colleagues want to program J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti, for example, I know the weight and gravitas that particular work holds. I can then passionately and intelligently write a project narrative for a grant without having to check in with my artistic team. Small things like being able to spell Tchaikovsky or Smetana, or knowing Beethoven’s year of birth and death without having to double and triple check for accuracy drastically cuts down on writing time. (I don’t know Shakespeare’s dates off the top of my head…)

Personal Connections

A substantial part of my job as the executive director of a classical music organization is making personal connections with donors and audience members. Not once has a conversation with an audience member at intermission covered digital marketing, social media strategy, or data management. I have however, found myself in deep meaningful conversations about a shared passion: music. The ability to speak genuinely about Bach, Chopin, or Shostakovich reflects commitment to the art form, and the fact that presenting concerts is not simply a day job for me. The same holds true behind the scenes when meeting musicians and artists. Spending time backstage with the likes of Bobby McFerrin, Richard Goode, or Chick Corea are some of the most rewarding moments of my career, which were made all the more special due to our shared zeal for the art.

Work and Play

Admittedly the line between work and leisure is indisputably blurred, which is not necessarily a bad thing! Even while I was a student and before my first real job in arts administration, I would spent my free evenings at concerts and performances. So why would that change now that I work within the industry? So of course I still love going to live concerts, but now there are many more facets beyond the music itself that I appreciate. Gathering innovative ideas, keeping tabs on up and coming talent, and networking with my colleagues all benefit me as an effective administrator. If attending a concert feels like a chore or obligation, then your workday will no doubt feel like a 12-hour marathon by then end of an evening.

There was a definite turning point in my concert going life about six months after my first job in the arts. I vividly remember sitting in Avery Fisher Hall, about to hear the Verdi Requiem performed live for the first time. Rather than sitting in the hall, eagerly anticipating the opening Kyrie, I remember thinking for the first time “Wow, how much did this cost?” From that point on, I have never had a pure concert experience where I can show up to a performance and simply appreciate the music. My administrator gears kick in and start calculating how much the soloist gets paid, what the program book cost, and a myriad of other managerial details.

Us versus Them

I feel fortunate to have spent the bulk of my career thus far in classical chamber music, an art form that I truly love and deeply appreciate. I am no less appreciative of larger forces as well, such as the symphony orchestra, ballet, or opera. But with larger forces also come larger problems and potentially larger rifts between the artistic and administrative teams. Much has already been written about the recent bankruptcies and labor disputes of venerable orchestras in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Chicago, Detroit, and Atlanta. At the time of this writing, the Minnesota Orchestra musicians have been on lockout for over eight months.

And what is the common denominator in many of these disputes? Money, of course, and what musicians see as fair pay for the services that they provide. The over simplification of this argument often boils down to this: musicians say “Well why can’t the Board of Directors raise more money?” and the administration saying “We cannot afford to pay this many musicians a full-time salary with benefits at current funding levels. Cuts have to be made.” Without getting into a prolonged discussion over who is right and how the problem should be fixed, it is worth noting the deep divide between the artistic and administrative sides of the equation. The administration must simply raise more money; the musicians must simply work for less.

As a musician and as an administrator my sympathies go out to both “sides”. Within my own organization it pains me to have to say, “we cannot afford that particular guest artist”, or “we need to scale back our December program from 12 musicians to 6”. It has been suggested to me on several occasions, “well can’t you just write another grant?” And as a pianist, I have been offered jobs on numerous occasions that pay below minimum wage, or that comes with no fee whatsoever (I’ll play for a few free drinks, right?)

Coda

No doubt after this article is published, another idea will immediately spring to mind about how my piano training has helped me in my administrative duties. And that is part of the appeal of this student’s question; just how many possible answers there are, and how will they evolve over time?

Marc Giosi is the Executive Director of Chatham Baroque and formerly served with Chamber Music America. He holds Masters and Bachelors degrees in piano performance, and has professionally performed on both the piano and the harpsichord.

*****

Articles of Related Interest from The Muse Dialogue:

“Tweets, Texts and Tchaikovsky” by Marc Giosi

“The Power of Will, The Power of Genius” by Kristine Rominski

“Seeking the Love of Music That I Once Felt” by Erin Yanacek

“A Question of Arts Survival” by Andrew Swensen

Excellent explication of the role of artist as administrator. Particularly keen insight about how ones appreciation of live performance can change (skewed?) after one have had to deal with the labor / management / costs issues yourself. Bravo Marc!